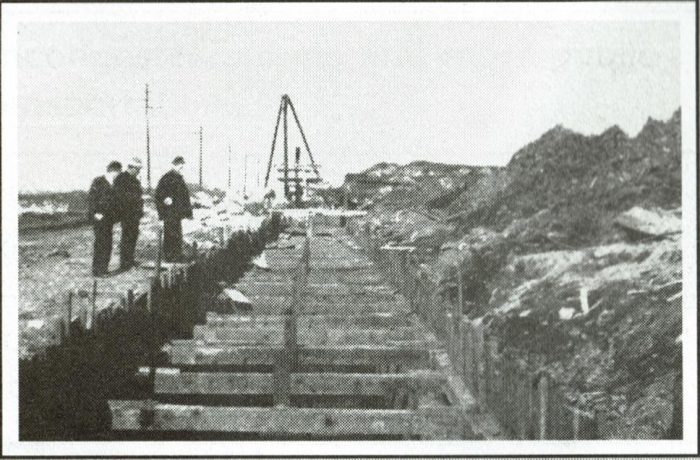

Unseparated Somerville sewer lines built in the 1880s remain in service

“Somerville’s municipal buildings, roads, sidewalks, water distribution, sewer collection, and stormwater management systems are all approaching the end of their intended lifespans.”

Part 1: Dimensions of the challenge

For generations our city’s infrastructure has slowly disintegrated while our leaders have budgeted for expenditures that appeared to be more pressing and were certainly more popular. Meanwhile repair and replacement costs steadily increased and accumulated. The bills are now coming due, and the amounts that we need to invest are jaw-dropping.

In a little noticed memo sent to the City Council in March, Richard Raiche explained how “Somerville’s municipal buildings, roads, sidewalks, water distribution, sewer collection, and stormwater management systems are all approaching the end of their intended lifespans.”

Mr. Raiche is Director of Infrastructure and Asset Management (IAM) for the City. In objective and dispassionate language he detailed not only our infrastructure’s frail condition, but that “many of those systems fail to meet current code, regulatory, environmental and general level-of-service requirements for a modern city” and must be reconfigured at enormous cost.

Municipal and school buildings

Extensive assessment of city buildings finds that to merely correct their fair-to-poor condition and bring them into code compliance would cost $300 million, of which $100 million is considered to be “emergency” or “high priority” expenditures.

But those are estimates of only what is needed to achieve nominal condition for existing facilities, most of which are inadequate to support city workers’ full productivity or the most effective delivery of city services to the public.

A Building Master Plan Working Group rated city buildings’ capacity to support city departments’ functioning on a 1-to-5 scale. None scored 5; 6% scored 4; and 60% scored 2.5 or lower. Constructing new facilities would optimize city departments’ functioning and, therefore, return on taxpayer dollars. But the cost would be a substantial multiple of $300 million.

Pavement and sidewalks

Somerville’s drivers and cyclists will not be surprised to learn that half our roads need full reconstruction. Another 30% need extensive maintenance to prevent their requiring full reconstruction. The estimated cost is $220 million.

But that $220 million is a fraction of the ultimate cost because our streets no longer meet our 21st Century needs for public transportation, cycling, pedestrian safety, ADA accessibility, stormwater management, urban forestry, and other public amenities. Reconfiguring them to do so would require much greater investment. Multiple city departments are collaborating on such plans.

Sanitary and Stormwater Drainage

Somerville began building its current sewer system in the 1880s and completed most of it before 1920. The gradual disintegration of this century-old system is producing hefty emergency-repair costs. Preventing continual escalation of these emergencies would require about a $100 million investment.

But that is a fraction of what we need, because only 10% of our land area has access to a dedicated stormwater system. Elsewhere in the city sanitary sewage and stormwater are drained by a combined system that flows into Alewife Brook and the Mystic River. So about every 3.5 years, basements in certain neighborhoods are flooded with raw sewage. And the City is quickly moving toward a regulatory deadline.

The successful 1983 Boston-Harbor-cleanup lawsuit brought by the Conservation Law Foundation produced a plan that all parties understood would not fully achieve mandated water quality goals by its December 31st 2015 end date. To meet those goals Somerville, Cambridge and the MWRA must submit a scope of work before this coming April. After comments and revisions, the plan must be finished by the end of 2023 and then implemented.

Much of our drainage system must be separated, also at great cost. But the Deer Island treatment plant can process a certain amount of stormwater—which contains its own pollutants—in addition to sewage.

So the challenge will be to determine what portion of our drainage infrastructure must be replaced by separate systems, versus what need only be rehabilitated—and to persuade Cambridge and the MWRA of these conclusions. Mr. Raiche and his colleagues have anticipated these deadlines and are prepared to meet them. Now the rest of us must anticipate and prepare ourselves for the cost estimate for those lines that must be separated.

Water distribution system

Households, in my neighborhood at least, are becoming familiar with sediment in our water and volatile pressure. Bringing the city system to an acceptable condition would cost about $220 million.

Unlike the previous infrastructure categories, our water distribution system does not need to be substantially redesigned. It was originally sized to fight fires rather than to brush teeth, so volume and pressure requirements remain fairly stable.

But that doesn’t translate into lower capital expenses. Configuring the system for optimal performance would require an additional $280 million, for a total of a half billion dollars.

The findings in IAF’s “Program Improvement Request FY2022” are summarized in the following table.

Type |

Condition |

Configuration |

To Achieve Nominal Condition |

To Achieve Optimal Configuration |

City Buildings |

Fair to Poor |

Deficient |

$300M |

? |

Pavement & Sidewalks |

Poor |

Deficient |

$220 M |

? |

Sewer & Stormwater |

Extremely poor |

Extremely poor |

$100M |

? |

Water Distribution |

Fair to poor |

Fair to good |

$220 M |

$280M |

Simply bringing our infrastructure to a condition that can be relied upon to ensure consistent service, avoid emergencies, and meet code requirements would require about $840 million. Investment required to achieve already agreed upon goals and fully meet our 21st-Century needs would be several times that figure.

To convey some sense of the magnitude of this challenge, consider that Somerville’s most recently available Comprehensive Annual Financial Report shows our total noncurrent debt at $225 million. The profound fiscal and policy implications will be discussed in Part 2.