How immigrants and working-class people have been impacted by I-93, across the years

The Somerville Wire recently received a Kozik Environmental Justice Reporting Grant, through the National Press Foundation and the National Press Club Journalism Institute. This article is the fourth in a series about how roadways like I-93 and others in East Somerville have posed health risks to residents, many of whom are immigrants and working-class individuals. Not only do highways present barriers, dividing East Somerville from other neighborhoods, but residents face the prevalent threat of air and noise pollution. Advocates have said that this is not an accident. Here is a look at how this environmental justice community been affected, since the I-93 was first built.

(Somerville Wire) – East Somerville has always been a gateway for immigrant and working-class residents. While the ethnic and cultural background of the people living there has changed over time, it has maintained its identity as a home for foreign-born and low-income households. Since the 1970s, this community has been affected by the construction of the I-93 highway, whose building resulted in the displacement of many families in the neighborhood. Today, vulnerable and marginalized populations continue to experience the burden of the roadway, which threatens their health with air and noise pollution—leading the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs to describe the neighborhood as an environmental justice community.

Milla Maia moved to Somerville when she was about to turn nine years old. Originally from Brazil, she learned a new language, made friends, and was reunited with her parents, who had come to the country before her. Now, Maia works as a youth program coordinator for the Welcome Project, an organization that provides social services to immigrants. Many of her students have been involved in a study called HAFTRAP, or Home Air Filtration for Traffic-Related Air Pollution, and she frequently talks to them about the impact of the I-93, which stands fairly close to the Welcome Project’s offices. When she first started working at the nonprofit, she would lead a tour that included a walk to the highway, where they would discuss the air and sound pollution.

“One of the things that stayed with me was the sound barriers that they have,” said Maia. “The sound barriers are only on one side of the highway. It’s on the Ten Hills side of the highway. If you’re going towards Sullivan, the west side of the highway has the sound barriers, but the right side of the highway does not have the sound barriers. … On the right side of the highway, where there is no sound barrier, is where you find the Mystic Housing Development, and as you go more down, you find East Somerville, which has always been a part of Somerville where income is lower. When you look at the left side, it’s where you find politicians or police officers, people with higher income.” She added, “I will say that I know that for our students, when we do the tour and talk about this, it arouses a lot of feelings of, what is important to the city, or who is important?”

During the time of I-93’s construction, much of the immigrant population in East Somerville were Irish, Italian, and Portuguese. This population was mostly working class and did not have the political power to resist its development, in spite of solid activist efforts, said Warren Goldstein-Gelb, interim co-executive director of the Welcome Project. Immigrants from Brazil, El Salvador, and Haiti began coming in large numbers to Somerville in the 1980s, shaping the immigrant population that is now there today. While East Somerville has experienced different waves of immigrants, they have always been a vulnerable and underserved community, said Goldstein-Gelb.

Linda Sprague Martinez, a professor at Boston University’s School of Social Work, said that both income levels and immigrant status had roles to play in the building of the I-93.

“It’s class, it’s immigrant status, it’s all of those things,” said Sprague Martinez, “in terms of the population that the dominant culture values or devalues. Even if you look at, why is it that there was a sound wall that was constructed on the other side of the I-93, but not on the side where East Somerville sits? You look at political power and who has that, who has the ability to advocate.”

Doug Brugge is a professor at the University of Connecticut who formerly taught at Tufts University and was a part of the Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health Study. East Somerville has struggled with the health effects of the highway and currently qualifies as an environmental justice neighborhood, with its racial and ethnic minority populations and economic conditions.

“The highway has a dramatic effect on people who live near it. There’s air pollution, there’s noise, and it’s ugly. It devalues housing prices,” said Brugge. “The highway has a substantial impact on the people living there.” He added, “There are a number of air pollutants that are elevated next to highways, major roadways, and train tracks. … There is a large and convincing body of evidence that people who live near highways have worse health outcomes, from a whole range of things: asthma, heart attacks and strokes, neurological harm in children and elderly people. There’s a whole bunch, but that doesn’t tell you what it is about the highway. It could be the noise, it could be the lower socio-economic status of people living there. What we set out to do was to measure the air pollutants, especially one component, called ultrafine particles, and then test whether people who had higher exposures to that pollutant also had higher markers of inflammation in their blood. And that’s what we showed.”

According to Goldstein-Gelb, the highway that was constructed was never really meant to serve the interests of the community. Many suburbanites wanted easier access to the city of Boston, where they were working, and demanded better transportation. Sprague Martinez traced the original motivation behind the creation of the highway back to the needs of this population.

“The highways were designed to bring people from the suburbs into the city,” said Sprague Martinez. “When you look at most early transportation systems, whether they’re highways or trains, they were designed to bring people from the suburbs into the city. … That’s the thought. So even if you think of that, who are they carrying to the city and back out of the city, they were not poor people, not people of color, no immigrant communities. That’s not who our transportation systems in the United States were designed for.” She added, “That’s not to say that there were no people of color in the suburbs at the time, but there were very few, because of the way segregation and redlining worked.”

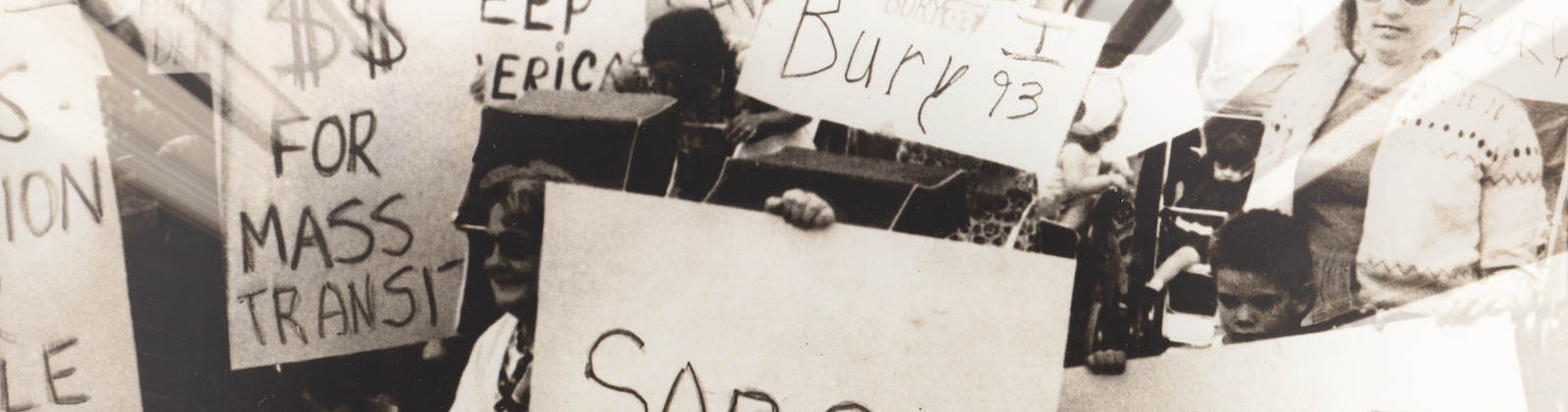

Dolores Lapiana, aunt of former mayoral candidate Mary Cassesso, lived in the Nunnery Grounds during the time when the highway was constructed. She was a steering committee member of the Somerville Citizens for Adequate Transportation, or SCAT, an East Somerville community group involved in activism. Lapapiana described how the working-class neighborhood was changed by the building of the highway, how houses were demolished and how people were displaced. Still, Lapiana remained in the neighborhood to see the roadway’s completion and her community permanently altered.

“It changed our quality of life,” said Lapiana. “I know everything that they talk about is lung problems and asthma. But you would not believe the number of cancer patients … My husband was one of them. He was a smoker, but there’s no rhyme or reason why people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, died of cancer. I know that the money and effort is because of asthma, heart conditions, and lung conditions, but someone should look at the cancer rate.” She added, “When these houses were demolished, these houses [had been] built in the early 1900s. There were asbestos boilers, and there were asbestos insulations around the pipes. You had to see it. They were demolished with everything in them. You could look out your window and see this. I attribute the cancer rate, and the asthma and heart conditions, to I-93. … What I get on my windowsill is not dust. It is soot. Every day, soot. All you have to do is rub your finger over the windowsill or the rails on the porch, and you get black soot.”

This article is syndicated by the Somerville Wire municipal news service of the Somerville News Garden project of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

All Somerville Wire articles may be republished by community news outlets free of charge with permission and by larger commercial news outlets for a fee. Republication requests and all other inquiries should be directed to somervillewire@binjonline.org. Somerville Wire articles are also syndicated by BINJ’s MassWire state news service at masswire.news.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE FREE SOMERVILLE WIRE EMAIL NEWSLETTER: https://eepurl.com/hpBYPv

Check out all our social media here: https://linktr.ee/SomervilleWire.

Shira Laucharoen is assistant director of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and assistant editor and staff reporter of the Somerville Wire.